In the first part, I wrote about discrimination and murder. Because of the limited time I have in my hands nowadays, I had to cut the article short, and wait for an opportunity to write the second part. In this part, I will try to point out a problem on which many articles have so far been written. This problem is often called “liberal pusillanimity.” In his article “Je suis Charlie? It’s a bit late,” Kenan Malik argues that the situation we are in today regarding free speech is the result of the self-censorship culture developed by many people who call themselves liberals. According to Malik, had such people shown stronger support for free speech for the last 20 years, we would not be dealing with most of the problems we have right now. This “pusillanimity” presents itself in a few different manners, including the ones that are subjects of this article.

The Obligation to Include and/or Compare

Discussions on free speech throughout history usually changed focus in each decade or so. Today, what we are faced with is “cuteness in consistency and objectivity”. Even the guy in the street, the dude in the supermarket, or the lady passing by behaves like an academic. Because of this self-censorship culture Malik is talking about, people feel the pressure to talk about everything that might be remotely relevant to a discussion, in order to “gain” the right to make the shortest but most personal, honest comment they have in mind. Just like writing an academic article that somehow needs to be constructed objectively on a really broad subject, they try everything to include anything that might be relevant, as they are consciously or subconsciously afraid of people who might say “but there is this, and there is that”. So, whatever context they might be in, however they might be communicating their opinions to other people, they use sentences like

*their opinion*, but of course…. *the other side of the argument that is not essential to the communication of the particular opinion*

or like

*their opinion*, on the other hand, *an issue that is similar to the particular issue of discussion, just to prove reliability*.

This is not a healthy way of communication. This happens probably as a result of people’s tendency to try to seem acceptable, correct, rightful or consistent. Even with the claim of “objectivity”, the argument ends up in “fake neutrality” at most. Arguing the right to freedom of speech should be subject to conditions is another problem, but here, we are just promoting intolerance. What if the Person A is not consistent? What if they are a bad person? What if the “remotely relevant” thing that is thought to be required in order to gain social acceptance contributes something to the discussion? Are we going to ignore the main idea, the thing Person A “actually” wants to say, among all the things they might feel the obligation to include? I think this is a waste of time, and the more people do this, the more it seems desirable to other people. So, after a point, the people who are equally rightful to “say things” become afraid of sharing their opinions, as they might be ignored or attacked because of not including something the society “wants to” hear. On the other hand, people with no respect for the right to freedom of speech get encouraged to gang up on other people who have not checked every single item on the hypothetical list of political correctness. This makes pure, uninterrupted, personal speech a thing that is much harder to have than politically correct, acceptable, “cute” speech.

One does not have to give an outline of Islamic history in order to have the right to make a comment on or criticise Islam. One does not have to first talk about immigration policies, discrimination or islamophobia in order to have the right to condemn terrorist attacks. One does not have to first talk about the attacks on abortion clinics in order to have the right to talk about the gender gap in employment in an Islamic country. Yet, people feel the need to do so. Yes, these things are relevant to the broader subject, and they might contribute to a broader discussion, but, do we really have that much time? Just going with the examples above, supporting Charlie Hebdo against terrorism has proved enough to be accused of “islamophobia” in many countries including mine. Anyone who did not include “yes, but, the rise of discrimination and hate in Europe”, “yes, but the imperialist powers that contributed to the suffering of Muslims in the Middle-East”, or “yes, but we should also not ignore the attacks in Nigeria/Pakistan/etc.” in their speech was accused of hating Muslims, being insensitive of other important issues, or simply taking a dirty, unjustified pleasure from other people’s suffering. Supporting an obligation of political correctness makes it harder for people to understand that talking about France does not mean one is oblivious to Nigeria, or talking about islamist violence without listing everything that might be relevant does not mean one supports or does not care about discrimination and hate against Muslims. Actually, most of the time, such “values” or “stances” are just “given” in the context. That people feel the obligation to include these just shows how terrible our world is, and that we still have a long way to go on these issues.

The Need to not Offend

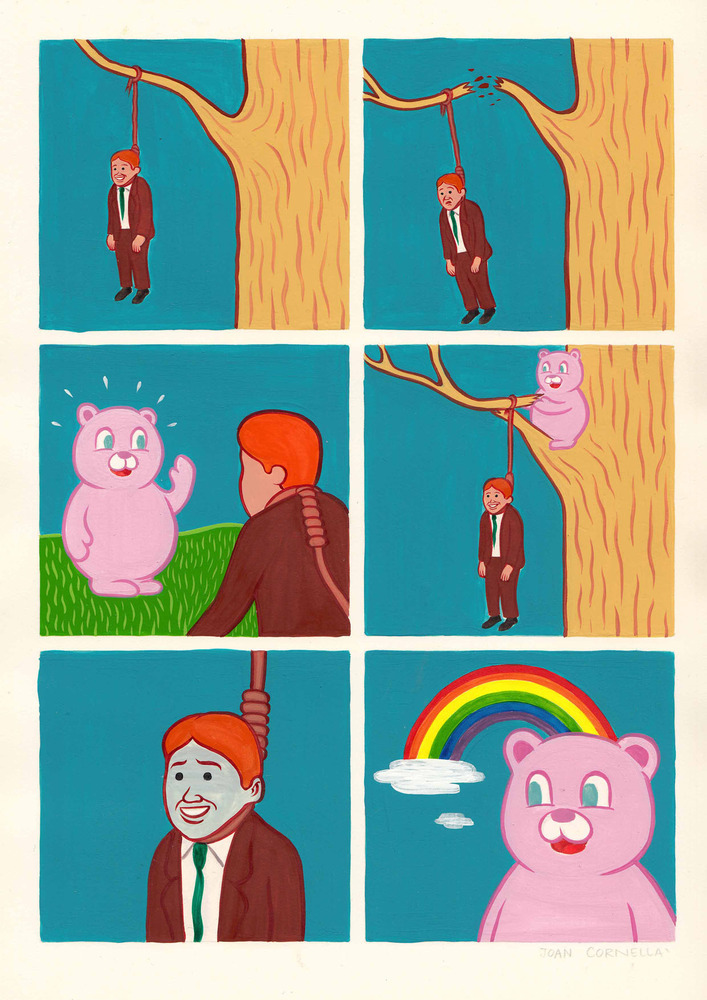

The disgusting and cowardly culture of political correctness and self-censorship makes achieving a sensible culture based on freedom and democracy harder. Freedom of speech has nothing to do with cute, lovely, acceptable expression. If everyone said cute, acceptable, favourable things, we would not need such a right. The mere existence of such a right depends on the existence of disliked, offensive, unfavourable, shocking or disturbing speech, as we can already say anything nice without any problems. The “only” purpose of the introduction of such a right is to protect the “ugly” speech, not “cute” speech. Cute speech does not need protection. No one is emotionally disturbed or offended by the sentence “I like apples” in a daily context.

By promoting a self-censoring concept like political correctness in the name of politeness, respect or peace, we have so far achieved the exact opposite of politeness, respect and peace. If anything, our obligation, or duty as humanity should be “to offend”, rather than “not to offend”, so that people can understand that our words cannot be more dangerous, hurtful, or unacceptable than their sticks and stones. Freedom of speech can exist without respect, politeness or peace, but none of these concepts and attitudes can exist without freedom of speech. The right to freedom of speech is -in my opinion- the most important human right, one even more important than the right to life, because one cannot even express support or demand for the right to life without it. We are people, and we are a civilisation because we can communicate. We are not a civilisation, we are nothing, if we do not have a voice.

So, it is not only a right, but a need to offend people, to show people that primitive things like violence, oppression, and hate do not belong here in the year 2015. It is our duty to show people that intimidation does not work in a civilised society, and everyone has the right to have a voice. By restricting ourselves in the name of respect or politeness, we are at least partly justifying the idea that we would deserve violent retaliation if we were not respectful or polite. As long as we continue to support this artificial, dishonest, evasive culture of political correctness, people will continue to say things like “the attack on Charlie Hebdo was terrible, but they brought it upon themselves.” No one, not even slightly, not even a little bit deserves death because of something they said, drew or wrote.

If we are really civilised, the right to offend will be our key in solving local and global problems. It is not only a right, but also a need to verbally attack bad ideas, ugly concepts, and dangerous threats. Nothing is exempt from criticism. Nothing is too sacred to be made fun of. No one is important enough to deserve respect as default. Respect is earned, politeness is shown in social contexts, peace is constructed over interaction and mutual understanding. Hence, we must protect the only thing that is definitely, globally sacred: our right to have something to say and say it without intimidation, obligation or restriction. This is the only way “bad people” would eventually understand that we, as civilised people, solve our problems with words, not guns, bombs or human rights abuses.

Leave a Reply